“If a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” - Goodhart’s Law

A few years ago, we brought in a Developer Experience dashboard at a previous role. Overnight, one of my teams’ cycle time metric was cause for concern. The message from above was clear: lower this number. So we chopped up tickets, split stories smaller, and watched our average cycle time drop. The dashboard turned green. Everyone was happy.

Except customers saw no difference. Our output increased on paper, but the features we shipped weren’t more valuable, they just arrived in smaller boxes. Releases got marginally safer, but nothing fundamentally shifted.

This is DORA’s trap: it’s precise about delivery speed, but that precision masks the bigger question, are you shipping the right thing?

This post explores what DORA gets right, where it falls short, and how to use it effectively without losing sight of the bigger picture. I’ll share how I approach these metrics now, focusing on real outcomes rather than just chasing numbers.

What DORA Nails

DORA’s four metrics (deployment frequency, lead time, change failure rate, and time to restore) became the industry standard for a reason. They reveal whether your engineering system is healthy. If releases are infrequent, slow, or break things, these metrics expose the bottlenecks.

In teams where deployment feels risky, DORA focuses effort on the mechanics of reliable delivery. Teams who improve these numbers tend to build trust and psychological safety. You can’t move faster without letting people experiment and learn.

Where It Falls Short

But DORA is a speedometer, not a compass. Once cycle time becomes a target, it gets gamed. Teams split stories smaller, push unfinished work into side channels, or manipulate the process to make graphs trend upward.

You can improve your DORA dashboard without shipping anything that matters. There’s also diminishing returns. Going from monthly to weekly releases transforms a business. Reducing cycle time from two days to one? Customers won’t notice. Eventually, the real constraints live elsewhere.

Looking Wider: SPACE, Flow, and Context

This is why I never look at DORA alone. Frameworks like SPACE include satisfaction, collaboration, and daily engineering experience. Flow frameworks go further, mapping value from idea to customer, revealing blockages DORA misses.

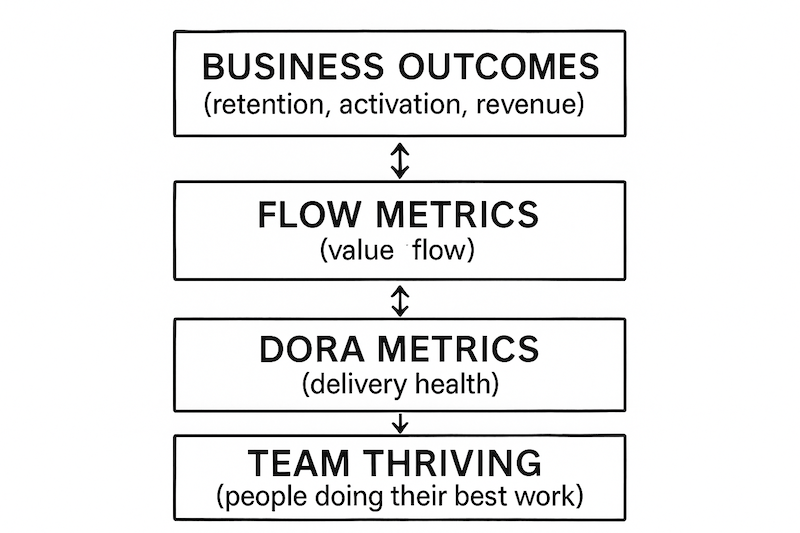

Personally, I believe a good measurement works in layers. At the top: business outcomes like retention, activation, revenue. These tell you if work made a difference. Below that, flow metrics show where value gets blocked, not just code. DORA sits underneath, signalling delivery health. At the foundation: is the team thriving or just burning down tickets?

If you only optimise one layer, you miss the full story. DORA is a great warning light, but business metrics tell you if you’re driving toward the right destination.

Avoiding Metric-Driven Thrash

Metrics work best as conversation starters. They highlight issues, not victories. The value is asking why a number moved, not just reacting.

Improvement requires a theory: a clear reason why a change will help engineers or the business. Skip that step and you chase what’s easy to count, not what matters.

I treat metric-driven changes as experiments. Make a change, watch what happens, check for real differences in customer engagement after a quarter. If faster deployments don’t shift outcomes, you’re measuring the wrong thing. If a metric just creates busywork (tickets close faster but nothing meaningful ships) kill it.

Teams don’t optimise for dashboards. They optimise for what gets celebrated. Changing incentives and making space for qualitative feedback matter more than perfect numbers.

How I Approach This Now

Now I anchor everything to one customer or business metric. DORA and flow metrics are early warnings. When they drift, dig deeper, don’t panic. In reviews, we examine what’s changing and whether it impacts customers. If code review takes hours but product discovery takes weeks, the constraint isn’t delivery.

Measurement should evolve with your team. If people game a metric, or it stops revealing insights, move on. The question isn’t “Are the numbers better?” It’s “Are we making a difference for customers, or just running in circles more efficiently?”

Benchmarks spot drift, but improvement happens locally. Metrics should open conversations, not dominate them. Without the story behind a number, you’re not ready to improve it.

DORA remains the quickest way to find delivery pain. But developer experience is about removing friction from work that matters. Stack your measurements: delivery, flow, outcomes, team health. Anchor them to impact, not activity. Otherwise, you’ll sprint faster toward nowhere.

Published on .